Pregnancy is a special time. And a special opportunity for malaria parasites.

Once bitten by an infected mosquito, a woman carrying a child is unlikely to experience malaria symptoms. The parasites make a bee-line for the placenta, rather than remaining in the blood, meaning the most common methods of identifying malaria infections—which rely on testing blood from a fingerprick—usually come up negative. In fact, there is evidence demonstrating that around 70% of malaria infections during pregnancy are missed by rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and assessment of blood samples by microscope.

So the parasites remain undetected, causing untold damage ranging from maternal anaemia to low birth weight—an important contributor to infant mortality. Dr Xavier Ding, Senior Scientific Officer at the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND), has been transfixed by this challenge. “The devastation that families face when the health of their baby is compromised before it is even born is deeply upsetting and unfair because it is, in theory, almost completely preventable,” said Dr Ding. “What we need, more than anything else, are tests that are sensitive enough to detect parasites in pregnant women but still easy to use in very minimally resourced health facilities.”

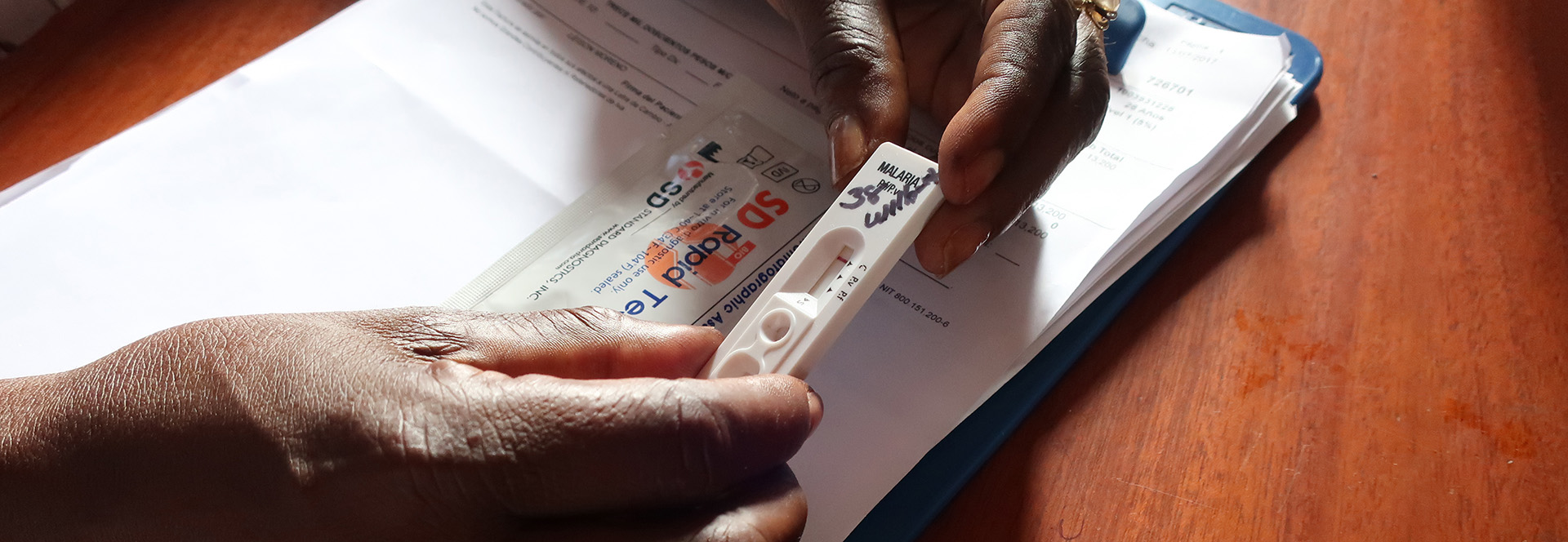

A new diagnostic approach could be an answer for expectant mothers. Dr Ding and his colleagues at FIND have been working with diagnostic manufacturers to develop new, highly sensitive tests. Several promising, innovative technologies have been developed and are in the process of being trialed. One is a rapid test that was created with Standard Diagnostics, with the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and PATH, which is ten times more sensitive than current RDTs when tested in the laboratory.

Dr Ding is excited to be partnering with the Papua New Guinea (PNG) Institute of Medical Research and the Burnet Institute, supported by the Australian government, to trial this new diagnostic in PNG. PNG is classified as a “low-transmission” country, where asymptomatic infections are common. The study will provide critical evidence about the performance of the new test and its capacity to improve detection—and therefore treatment—of malaria in pregnant women. If it is successful, the study could pave the way to policies recommending the use of such improved RDTs for the screening of pregnant women.